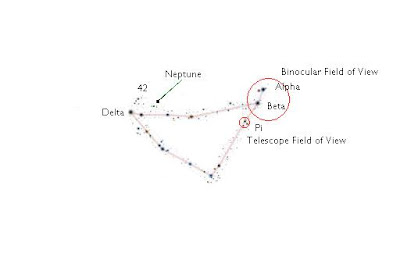

This is a photo of Capricornus I found on the Web. It was taken with a wide angle lens so the stars appear much closer together than they do in the sky. Below I’ve labeled some key stars, and I’ve indicated the very different sizes of what you see through binoculars compared through a telescope.

This is a photo of Capricornus I found on the Web. It was taken with a wide angle lens so the stars appear much closer together than they do in the sky. Below I’ve labeled some key stars, and I’ve indicated the very different sizes of what you see through binoculars compared through a telescope. Even with good skies here south of Chicago, almost all of these stars are invisible to the naked eye. Alpha and Beta are just barely visible. The rest are binocular objects. The three little stars labeled 42 Capricorni are the limits of binocular magnitude around here.

Even with good skies here south of Chicago, almost all of these stars are invisible to the naked eye. Alpha and Beta are just barely visible. The rest are binocular objects. The three little stars labeled 42 Capricorni are the limits of binocular magnitude around here.The four smaller ‘field stars’ to the right of 42 Capricorni are just barely visible through my 2.4 inch (60mm) telescope.

With binoculars it’s a piece of cake to find Alpha and Beta Capricorni, then drop down to the three stars around Pi Capricorni, and then follow the ragged trail of dim stars east to Delta and Gamma (Gamma is the bright star just right of Delta, unlabeled here). With binoculars the three stars above Delta, 42 Capricorni, are visible, but the sky around them appears bare, no field stars at all.

Turning a telescope to Capricornus brings a whole new set of problems.

The field of view of a telescope is only about 1 degree, compared to 5 or 6 degrees for binoculars. My telescope uses a small ‘finder’ scope (20mm) to find and point at celestial targets. Looking at Capricornus, however, most of the stars are so dim in the light-polluted skies above me that my finder scope cannot see them.

As if the bad sky overhead wasn’t challenging enough, my neighbors all have ‘security’ lights on their garages at night. Some are VERY bright. That glare flares against the objective of my finder scope, washing out some stars that are bright. I had to make a lens shield from a rolled up index card to even use my finder scope with low, southern views.

I had to start at Alpha and Beta with the finder scope, just as I did with binoculars. Then, cupping my hand around my finder scope eyepiece and my eye to shield my own vision from the night lights, I starhopped south to the three stars around Pi.

They were just barely visible in my finder scope.

Then I moved east. And got completely lost.

With binoculars it’s an easy jump to Delta and Gamma. But with the finder scope I had to position Pi very carefully at the top of my field of view, then move east very carefully, moving slightly south at the same time.

That got me to Delta and Gamma.

My finder scope couldn’t see 42 Capricorni above Delta, but they are close enough that at 36x I could move upward with my telescope itself from Delta to the three stars of 42 Capricorni.

From this point, I could no longer use binoculars or my finder scope. Only my telescope could resolve the guide stars leading to Neptune.

Moving back west from the bottom of the three stars above Delta (that is, of the three stars above Delta, starting from the star nearest Delta), there are two very dim stars that form a line. The two dim stars are almost one field for me, and moving west two of those fields along the 'line' of the two stars takes me to two even dimmer stars which also make up one field for me. And between those two very dim stars, is one slightly brighter point with a visible greenish tint.

Neptune.

The cool thing about observing planets is you can always tell when you’ve got the right target because, night by night, a planet moves against the backdrop of stars. Neptune was close to the eastern-most dim star when I first observed it. Now Neptune is almost directly between the two.

Neptune will continue retrograde right past the second guide star, then stop, and then come back toward and then past the first star.

Motion like that used to cause early astronomers (and some Church figures) to invent all manner of weird celestial mechanisms to try to explain what they saw. Of course, they couldn’t see Neptune, but Mars, Jupiter and Saturn—what we now call the ‘outer’ planets—all exhibit retrograde, ‘backward’ motion against the stars. It’s caused by our view from here on Earth, also moving around the Sun.

Blue And Green: The Alchemical Sky

Sometimes little things have an effect on us that seems to be way out of proportion to our expectations. (Inca Roads Pt. 1 and Inca Roads Pt. 2) Starhopping through Capricornus has been like that for me.

(A ‘road’ is something we travel to get from one place to another. I used Capricornus to get from Aquila to Aquarius. Capricornus has been a kind of real Inca road for me...)

A couple weeks back, when I first went looking for Uranus, I observed Beta Capricorni for the first time. I was struck by the subdued beauty of the double star: Bright white primary, with a very dim, very blue companion. Very beautiful. I was so struck by the color and brightness contrast that I did a pencil sketch and then an oil pastel sketch of the system.

It didn’t occur to me until I was typing up the first few paragraphs of today’s post, but Neptune in Capricornus makes a kind of diptych with Beta Capricorni B.

Beta Capricorni B is invisible to the eye and, in a telescope, appears as a tiny point that is beautifully blue.

Neptune is invisible to the eye and, in a telescope, appears as a tiny point that is beautifully green.

Astronomers and chemists typically don’t have a lot of kind words for astrologers and alchemists. One way of looking at the differences between scientists and pseudo-scientists is that scientists look at the universe and ask, “What can our knowledge of the universe tell us about the universe itself?” Whereas an astrologer or alchemist looks at the universe and asks, “What can our knowledge of the universe tell us about ourselves?”

The beautiful, invisible points of blue and green at opposite ends of Capricornus have been trying to tell me something, but I don’t even know if what they’re trying to tell me is about me or the universe.

I’ll be giving it more thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment